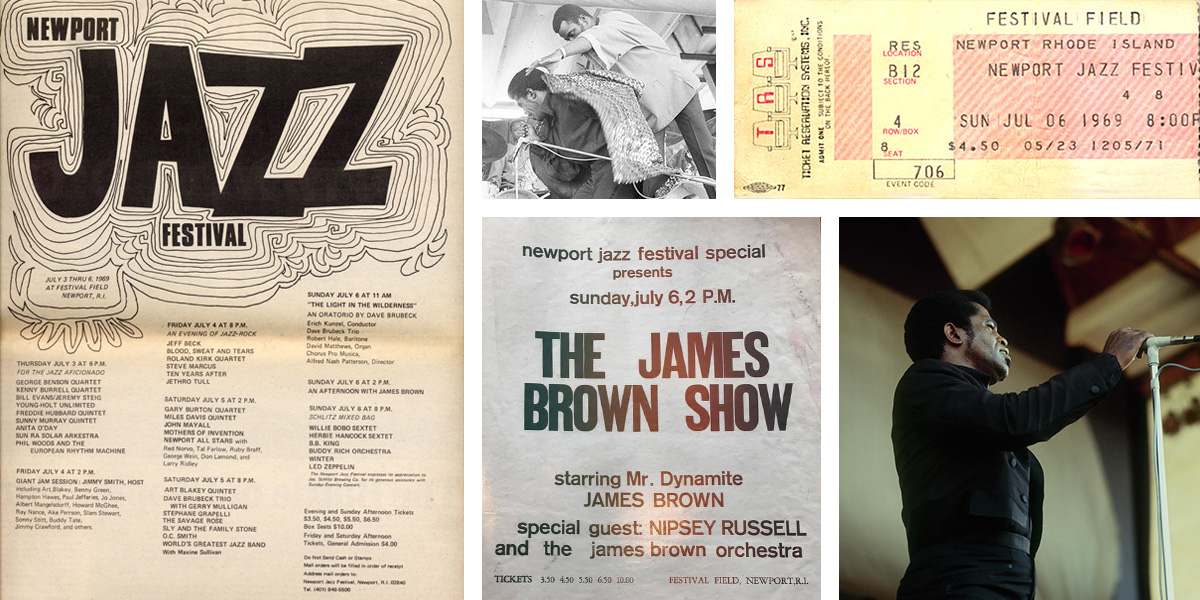

James Brown at Newport 1969

by Christian McBride

Photo by Tom Copi

I’m firmly convinced that from a musical standpoint, everything that happened in 1969 was incredible. Jazz, rock, soul, blues, Latin – just close your eyes and land your finger on any album that was released that year, and there’s at least a 50% chance that you’ll land on something pivotal.

What happens when the most pivotal, genre-busting artists perform at the most important music festival of all-time at a pivotal time in history?

Lots of Interesting stuff.

In 1969, the two hottest styles of music in America were rock and soul. Jazz was up against the ropes in terms of relevance to younger people like never before. To the beatniks a generation before, jazz was the music of the hip, artsy, wanna-be-street-smart rebels. Those same rebels now had families and responsibilities that kept them from hanging out like they used to. They grew up. The last thing they wanted to hear was some loud-ass screaming guitars – especially at the Newport Jazz Festival.

As a businessman, George Wein knew that if he wanted to keep his festival alive, he’d have to address the times. In an unprecedented move, George went all the way “mod”. It was the first time he’d changed the ratio of jazz vs. pop at his festival. George had always been 100% dedicated to the pulse of the grass roots of the jazz community. However, after lagging ticket sales in ‘67 & ‘68, George knew he had to do the inevitable. Never turning his back on the jazz community, he booked the pillars such as Miles Davis, Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, Dave Brubeck, the Jimmy Smith all-star jam, young bucks like Herbie Hancock and Freddie Hubbard, but the overwhelming majority of new fans that year came to see Sly & The Family Stone, Led Zeppelin, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, Jeff Beck, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Jethro Tull and Johnny Winter. The way these rock groups were creatively programmed in between people like Miles, Brubeck, Blakey, and Buddy Rich is pretty fascinating.

Back then, the four-day festival was split into halves – an afternoon program and an evening program. On Sunday, July 6th, only one person played that afternoon: Soul Brother Number One, James Brown.

Photo by David Redfern

There were few artists hotter than James Brown in the summer of 1969. As far as Black music was concerned, he had no competition. Sly Stone’s Q rating was right up there, but he hadn’t become quite the household name that he would be upon his appearance at the Woodstock festival, which hadn’t happened yet. Brown, however, was on a roll like he’d never been before. In many ways, he’d almost become the literal face of Black America, as his social anthem “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” was still atop the charts. He’d just bought a restaurant and his third radio station; he’d created “Black and Brown” stamps, which were similar to public assistance stamps (yes, the man was basically printing his own money!); he’d controversially performed at President Nixon’s inauguration; and his newest hit single “Mother Popcorn”, which had started the last dance craze of the 60’s, had just hit #1 on the R&B charts and #11 on the pop charts two weeks before his appearance at Newport. Good timing, I’d say!

When I first heard a recording of Brown at Newport, I thought at first, he sounded a shade tired. Thanks to my friend, and former JB tour manager and archivist, Alan Leeds, I checked Brown’s schedule leading up to Newport. On July 4th, he played a sold-out concert in New York at Madison Square Garden. On July 5th, he played a sold-out concert in Philadelphia at The Spectrum (a concert produced by George Wein, by the way ). His band got back on the bus after the show in Philly (I would guess at around 3AM) and drove 274 miles to Newport to prepare for a 2pm show. After the show in Newport, the band got back on the bus (JB flew in his private jet, of course) and drove 844 miles to Cincinnati, where a fresh and rested Brown immediately took them into the studio.

If you ever saw James Brown and his band live, especially back then, you know that you should not judge them as musicians, but almost as athletes. When James Brown performed, he yelled, he screamed, he moved, he sang hard, he danced hard, and he made his band work as hard as him. To do back to back to backs on a regular basis was grueling. Even pro basketball players rarely did as many back to backs as James Brown did. Not to mention, pro basketball players only played one game per night. When Brown and his band would play the Apollo, Uptown, Regal, Howard, or Royal Theaters, they’d often do up to four or five shows per day! It’s unfathomable that Brown’s voice was able to maintain any sort of tonal center by his 40’s. If you could equate his body to a car, by the time 1969 came around, he’d put about 500K miles on himself – and still had all the original parts intact.

I (sort of) love hearing stories about how Brown would often play two cities in a day. A Toledo show at 2pm and Cincinnati at 7pm? No problem. San Francisco and Sacramento same day? Nothing. Newark at 7pm and Philly at midnight? Book it. These were not musicians getting onstage in comfortable clothing taking their time to figure out what songs to play, build their long solos, and relax on the side while the rest of the band plays. We’re talking about a memorized two-hour revue with choreography, costume changes, and body cues from a temperamental and tempestuous bandleader.

Never judge those old-schoolers. We’ll never understand.

Photo by Julie Snow

But because of this almost inhumane work schedule, run by an other-worldly bandleader, James Brown had singularly carved out a rep as having the best show in the business. This is why he was the only performer that Sunday afternoon. It was packed. Hardcore jazz fans, soul fans, rock fans, even gospel fans knew that seeing James Brown was an experience. The band was at their peak – Alfred “Pee Wee” Ellis (alto sax & bandleader), Fred Wesley (trombone), Maceo Parker (tenor sax), Richard “Kush” Griffith, Joe Davis (trumpets), St. Clair Pinckney (tenor & bari sax), Jimmy Nolen (guitars), Alfonzo “Country” Kellum (guitars), Charles Sherrell (bass), and the Holy Trinity of funk drumming all in the same band – Clyde Stubblefield, John “Jabo” Starks, and Maceo’s older brother, Melvin Parker. Yes, you read that correctly. JB had three drummers. Why? Each drummer had such a distinct sound and feel for certain songs, he had to have all three. But I also believe a little pragmatism was at play. The James Brown Show was so physically grueling, one drummer would never be able to carry the entire load. The way Brown would switch drummers in the middle of the song was often like watching a hockey team do a line change.

James Brown Live at Newport 1969

There are multiple audio recordings of Brown’s Newport set on YouTube. It’s an incomplete recording as only part of the band’s instrumental set and Brown’s set were captured. Also part of the Brown revue that day was vocalist Marva Whitney and comedian Nipsey Russell, who was already quite a well-respected, veteran comic in his own right.

Brown opens his own teaser set with “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud).” I would love nothing more than to time travel back to that day to see all those Newport Jazz Fest regulars shout back, “I’M BLACK AND I’M PROUD!!!” After tearing through “Say It Loud”, Brown immediately simmers it down to sing his always soulful rendition of “If I Ruled The World.” Mr. Brown then gets to his blues & jazz roots with “Kansas City”. Usually, after “Kansas City,” Marva Whitney would come out and do her set. Unfortunately, that did not make it to the recording. After Marva Whitney, it would be time for the comedian. Clay Tyson had been the official comedian on the James Brown Show for many years, but Brown was on such a roll, he added another legend to his show in Nipsey Russell, who had also joined him in New York and Philly, two days prior to the Newport show. After the band would play a few more tunes, it was now Star Time Brown was now back onstage in full ‘Tasmanian Devil’ mode. This is where the audience should have been granted a safety warning.

Sadly, the Star Time intro was lost, as well as the first few minutes of “Licking Stick”, but the rest of the set is intact. I’m not going to give you a full detail of the set, but I will say that after the show’s finale – an 8-minute version of his then-latest smash, “Mother Popcorn,” the audience had been officially slayed. As you can hear the audience’s profuse cheering for about two minutes, Brown comes back and sings three more minutes of “Mother Popcorn.” The audience did not want him to leave. But alas, the king needed to prepare to slay more audiences…and an era.

James Brown at the 1969 Newport Jazz Festival was an event.